|

Earlier this month we had our Fall Parent Evening, “Cookies and Connections” (and we proudly did figure out a way to safely send everyone home with some cookies to keep the theme alive, even amidst a pandemic!) We took a gamble and decided to hold this adults-only event in person, as opposed to the Zoom evening we’d hosted last year. And I am so glad we did, as it truly gave the adults in our community a chance to connect, with each other and with the space that our children inhabit throughout the school day. Parents were happy to comply with our vaccination and health attestation policies, and as the night went on everyone seemed more comfortable, though perhaps a bit out of practice, being at school in person together.

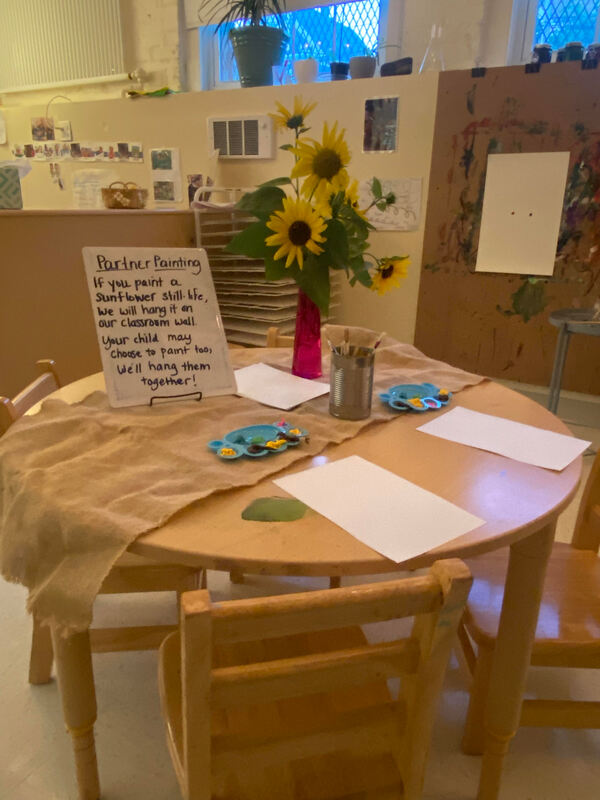

One parent said to me, “as I arrived at the building, I suddenly had a realization, ‘wait a minute, this is a social event. Am I up for this?’” but then reflected that she was ultimately glad she’d decided that she was. After so long spent apart and interacting with each other through screens, we are all learning how to be in the same room together again, and, just like for our children, these social interactions take practice, thought, and effort. But the classrooms felt warm and welcoming and the parents seemed at ease inhabiting their children’s spaces. In one classroom two parents sat together painting sunflowers, anticipating their children viewing their artwork the next day; in another a small group sat together writing out their children’s “name stories.” When I made it to my son’s classroom, the mood was relaxed and joyful, teachers and parents sitting in a circle on the ground sharing stories about their children. I was happy to put on my “parent hat” and join the conversation! At the end of the night, and as I’ve reflected on the evening since then, one moment from that conversation has stood out to me. A parent, in an innocuous offhanded way, referred to her toddler as “bossy” and a teacher agreed, “in a good way, of course,” and we all laughed it off. I have long thought that I don’t like the word “bossy,” and it’s taken me awhile to figure out what it is about this simple word that consistently rubs me the wrong way. I’ve realized that I have never heard a boy referred to as “bossy,” yet my entire life I have heard this term used to describe outgoing and opinionated young girls more often that I can count (myself included). When you dissect the root of the word, it essentially means acting like a “boss,” which in itself is not necessarily a negative thing. However over time the word has come to mean domineering, ordering others around, and has a distinctly female-leaning connotation. In fact, when you search for definitions and samples of the word as used, the subject is always a woman. “Bossy” men seem to be more often described as “authoritative,” “decisive,” or “take-charge,” words which certainly seem to have a more positive lilt to them in modern dialogue. Noting this distinction has made me think more deeply about what words I am using regularly with young children, and what those words teach them about themselves, each other, and how their identity is viewed in the world around them. Earlier this Fall, I challenged our teachers to notice and minimize their use of gendered language in their classrooms this year; this is partly because it has been shown to be best practice in helping children develop their own sense of identity at a young age, with as little influence from social biases as possible, and partly because it is an eye-opening research experiment, in noticing how much of the language we use in conversation on a daily basis is in fact, often unintentionally, heavily gendered. In progressive early education it has become best practice to minimize the use of gendered language; for example, you may notice many preschool teachers using the traditionally Quaker manner of referring to students and classmates all as “friends,” rather than the more conventional “boys and girls.” However, there are still so many, sometimes subtle and sometimes explicit, ways in which socially accepted gender constructs and stereotypes make their way into our interactions with our youngest learners, and when we start to actively look for and question this language, it becomes clear that there is in fact a way to shift this cultural construct. In general, I prefer my interactions with young students to focus little on gender, and I try to use as little gendered language as possible, especially because I have had students in my classes before who were gender-questioning or already knew that they did not fit neatly into the male-female gender binary. One year, however, my co-teachers and I decided to make a point of taking all gendered language out of our conversations with one another and our students, and it became a kind of social experiment in which we called out each other and ourselves throughout the school day for using gendered language. The most enlightening part of this “experiment” was that we each suddenly realized how often gendered language really does creep into our speech and interactions with others, and the act of noticing also made us reflect more thoughtfully on when and how we used such language. For example, even if you are not someone who frequently uses overly gendered terms, such as addressing young girls as “pretty princesses” or referring to young boys as “brave superheroes,” you may start to notice different, more subtle, gender expectations embedded in the language you are using with children. When you ask a child to do something themselves, because it’s what a “big kid” would do, are you saying “be a big boy and carry your own backpack,” or offering praise to a “good girl” for staying quiet in public? Do we subtly provide different expectations for girls and boys that come through in our gendered language, such as when we comment, with well-intentioned kindness, on a young girl’s lovely clothes or appearance, and compliment a young boy for his strength and agility on the playground? Individually, innocent comments like these may not have an effect on our children, but when layer upon layer of interactions such as these are piled upon our youngest learners, girls start to believe that their value lies in their appearance, and boys start to believe that their voices and needs should be louder and matter more and overpower those of others. We don’t mean to pretend that gender does not exist, and we don’t attempt to completely keep it out of our classroom environments in every instance. It is inevitable that conversations about gender as a social construct and physical gender differences will come up frequently within an early childhood setting. However, we make a point of defining each other and our students by many other qualities; a person’s gender is only one aspect of who that person is, and there are so many other parts of their personality on which we can focus when discussing whom we enjoy spending time with and why. When we frequently model this inclusive and respectful language and behavior, it encourages our children to do the same. I am so grateful for this community now more than ever, and the chances it affords for both our children and us adults to come together and connect, socialize, and thoughtfully practice and reflect upon these important social language skills regularly, especially in a world that feels so isolated at the moment with so much of our connection happening through screens.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Anna Goodkind

Archives

June 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed